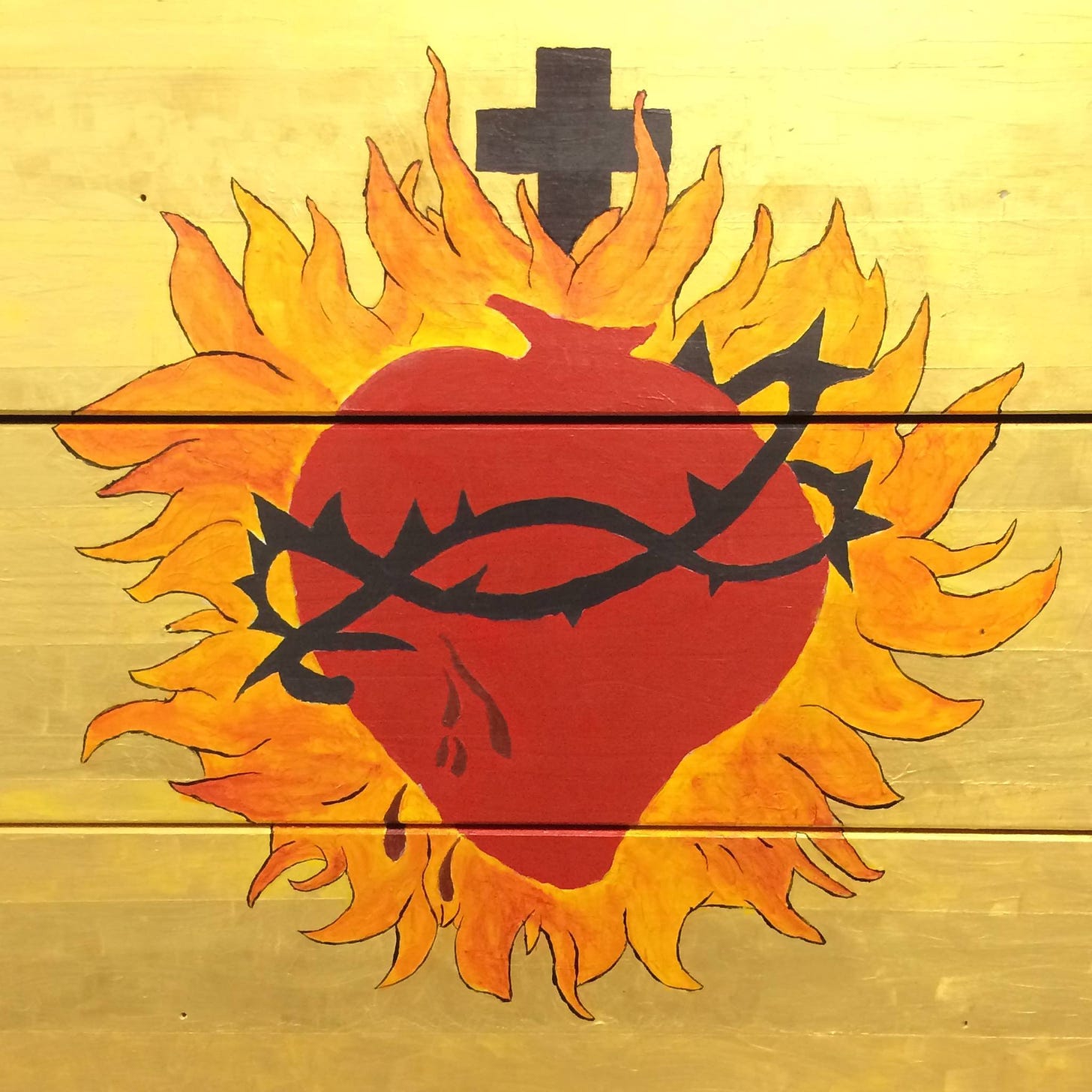

Sacred Heart Dresser (detail), 2016. Colin O’Brien, acrylic on wooden dresser.

The only major surgery I’ve ever undergone took place when I was two weeks old. I had been vomiting, and on the Sunday evening of Labor Day weekend, I started choking. My parents rushed me to a hospital, where an emegency surgery was performed on my abdomen to cut the pyloric muscle controlling the passage of from from the stomach to the small intestine. The surgical scar grew with me, a daily reminder of how close I came to death all those years ago.

For as long as I can remember, I knew of this near-death experience. I derived a sense that I was sent for a purpose and that I had not died because I had not yet completed what I was sent to do. Despite the hardship and fear and loneliness of childhood, I had a deep intuition that God loved me and was looking out for me.

I had a simple faith — I was not particularly well catechized and I did not know many prayers other than the Lord’s Prayer, but I very much liked the beautiful, dimly-lit church in the parish where I grew up. It was an immense brick building with a wooden barrel vaulted ceiling that seemed as high as the sky to little me.

I would go to Mass with my mother sometimes; other times at about age 6 or 7 perhaps, I would occasionally walk there alone for Sunday Mass. We would go as a family to midnight Mass on Christmas eve, and also to the Easter Vigil. I always loved hearing the reading from Exodus, where the Red Sea closed back upon Pharaoh’s chariots and charioteers.

My grandfather, a diminutive Irish-American pipefitter who attended daily Mass in retirement, and a beloved great aunt who was a Franciscan sister for over 60 years when she died were two gentle and loving models of faith for me. Though I was never as devout or diligent in practicing my young faith as they were, I experienced the Church as a home, a place of quiet refuge. As an adult, I learned that the first thing I wrote when I was learning my letters was “I LOVE YOU GOD” on a piece of paper that my mother kept and placed in a scrapbook for me.

The simple faith and deep sense that I had a yet-to-be discovered mission lurked beneath the surface, periodically emerging in times of fear or loneliness or distress. Once during junior high school when I was sitting at a bus stop on an afternoon after school, a car stopped at the red light about ten feet from me. The passenger put the window down and pointed a pistol at me.

Oddly, I did not experience any fear or anxiety. Instead, I had a deep intuition that nothing was going to harm me because I had not yet accomplished what I’d been sent to do. I simply sat there on the bench, glaring at the man as the light changed and the car drove on. He pulled the trigger and I heard a loud POP! but nothing happened. I assume that it was a cap gun and not an actual weapon; this was in days before toy guns were manufactured in bright colors to be clearly distinguishable from firearms.

Several years later, in high school, a friend and I were in a rather severe-looking car accident. The vehicle we were in rolled over on its side in a busy intersection a couple blocks from my mother’s house. Fortunately, neither of us sustained any injuries. Grateful for my being uninjured and at a bit of a loss for what to do, since my mother was at work, I took the bus to downtown Minneapolis and went to sit in the cool, dimly lit nave of the Basilica of Saint Mary. Despite not having a very learned faith, there was something comforting about sitting there in silence and giving thanks for being safely delivered from a potentially disastrous wreck. Coincidentally, a Mass started about a half hour after I arrived. Consolation found me without my planning for it.

I must have been in about 2nd grade or so when I asked a difficult question in CCD class. We were learning about the Golden Rule that evening, and I, already a grim little philosopher, asked a provocative question.

“What if you don’t love yourself?” Honestly, I truly wanted to know, I was not merely trying to be a gadfly. Our teacher was stumped.

Two decades or so later, after I’d returned to the Church and started to go to Mass regularly and pray and read the Bible, I got the answer that 8 year old me wanted.

“As I have loved you, so you also should love one another” (John 13:34).

The subtle but important truth of Christ is that He came, not merely to impose a moral code, but rather to fully reveal God’s love for us. By basing His new commandment upon His love for us rather than our love for ourselves, He gets around our own smallness, our own brokenness. By calling to mind His love for us, we come to see a stark and humbling truth: living in His infinite love for us means we are now deprived the luxury of self-hatred.

This love comes to us, not because we've somehow earned it by being good, by remaining pure, or by having a deep intellectual grasp of truth, but because He wants us to be closely united with Him.

Our sins and shortcomings, therefore, do not diminish God’s love for us. Rather, they impede our ability to receive His love and to love others as He loves us. “If you love me,” He says, “keep my commandments.” It is not, “if you keep my commandments, I will love you.”

With God’s love for us rather than our ability to conduct ourselves with flawless morality as the operative principle of our relationship with God, we are liberated from anxiety over or our sins and failings and instead invited to reflect with gratitude and wonder at God’s merciful love for us.

St. Bernard of Clairvaux, one of the Church’s most astute psychologists, addresses a practical yet pressing question that poses a stumbling hazard for people of faith. In his Sermon on Conversion to Clerics, he addresses the quesiton of memory: If God has forgiven my sins, why do I still remember the sins I committed? If I’d truly been forgiven, would I not have my memory of those acts erased?

God’s mercy and forgiveness takes away sin but leaves memory intact, of both the sins we’ve committed and those that others have committed against us. Memories of our sins can be turned to good account — they invite us to give thanks for the forgiveness we’ve received. In the economy of God’s love, these memories turn from causes of sorrow and distress to invitations to greater intimacy with God. Memories of the sins others have committed against us do us no harm, as we are not accountable for those acts.

This astute and sensitive discussion of memory was the passage that endeared St. Bernard to me, and hence, by extension, the medieval Cistercians in general and their spiritual sons and daughters of today. From there I read more of Bernard’s works, as well as those of his confreres, and ultimately went to discern my own monastic vocation with the Trappists.

In confronting many painful and troubling memories of both things I’ve done and things others have done to me, I’ve experienced great pain and sorrow. To be reminded first that memories of my own sins aren’t meant as accusations or evidence that I’m not loved or forgiven but rather invitations to enter more closely into God’s love are a warm reassurance.

More recently in writing and reflecting on the far-reaching consequences of the sins of others against me, I have come to understand what Bernard means when he says that the memories of others’ sins do us know harm. By taking moralism out of my reaction to being assaulted, for example, I see clearly that my adolescent physical response was not a soul-endangering sin on my part, but instead was the natural and healthy reaction to the actions of an adult who ought to have known better. The anxiety and self-hatred are slowly giving way to a greater love of God.

After all, by going into my dark places of memory with the light of Christ, I truly see His love for me.

PS: In his recently-issued encyclical Dilexit Nos on the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Pope Francis cites Bernard as one of the saints who saw Jesus’ love and mercy in His wounds, in His pierced side.

The document itself is long and demands a thoughtful reading, so for now I will not elaborate until I’ve given it the attentive reading it deserves. I already see points I wish to elaborate on in subsequent articles.